By Kunda Dixit*

TOKYO, Oct 11 (TerraViva) – The world may be in economic crisis, Asian growth may be stumbling, and Japan may be suffering a slowdown, but you wouldn’t be able to tell in glittering Tokyo this week as it hosts the Annual Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF.

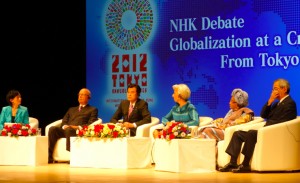

There is a sense of normalcy in the streets outside, as if all is well with the world and it is business as usual. But inside the conference venue at the Tokyo International Forum, there is a pall of gloom as it debates the impact of the European crisis, the slow recovery in the US, the absence of China from the meeting, even questions about whether globalisation has been the panacea that the ‘Washington Consensus’ always said it was.

The Annual Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF are held in Washington every two years, but every alternative year they take place in a developing country. Bangkok, Istanbul, New Delhi have all had their turns. But in recent years as anti-globalisation protests have become more organised and vigorous, the conferences have been located in places like Dubai and Singapore, which have banned all street protests. This year’s meeting was supposed to take place in Egypt, but due to the volatile political situation it was shifted to Tokyo.

The streets around the conference venue in Tokyo have a heavy, but discreet, security presence with busloads of police parked along the fringes of Hibiya Park. But for those who have come to associate water cannons and tear gas with World Bank-IMF meetings, this one so far doesn’t have them.

The World Bank has returned to Tokyo after 48 years. The last time the city hosted the meeting was in 1964, the year Japan also hosted the Olympics. The country was in the process of rebuilding, and 20 years after the end of the war it was on track to recovery and had regained confidence in itself. Much of that restoration was carried out with the help of the World Bank.

In the early years, the Bank was involved in infrastructure and energy. Its first loan in 1953 was to build thermal and hydroelectric power plants below 100 megawatts, the kind of energy projects that the Bank is now involved in in poor developing countries. It was a World Bank loan that helped build the first Bullet Train line, and it forced Japanese engineers to scale down the project so that the trains would run at 200 mph instead of 250 mph. Bank consultants also wanted the trains to carry freight at night to make them feasible, which the Japanese rejected. The World Bank

loaned money for the Toyota assembly line and for the first intercity expressways in 1960, which was later expanded to one of the most modern road networks in the world.

The World Bank then invested in Japanese bonds and tapped Japan’s economic growth to generate cash to reinvest in other developing countries in Asia, like China, Indonesia and Thailand. As World Bank President Jim Yong Kim reminded his audience here on Thursday, 60 years later, Japan has turned from a borrower to being the third biggest donor to the World Bank.

This week, as 22,000 delegates from 188 countries gather in Tokyo to look at the global economic slowdown, it has also turned attention to how catalytic lending can work in averting crisis and building prosperity.

But there is a sense that Japan is also coming full circle as it struggles with second-generation problems of an ageing population, recession and a future fiscal emergency.

*Dateline Earth is a column written by Kunda Dixit, editor and publisher of ‘The Nepali Times’ during this TerraViva edition.

(END/TV/IPS Asia-Pacific)