By Roberto Savio*

The 1992 Earth Summit was one of the great moments of collective optimism. Maurice Strong of Canada, who founded the U.N. Environment Programme, managed to move on three fronts simultaneously. First, the customary one, was to call together the heads of state.

The second, novel one was achieving the participation of large companies, through the creation of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, because without a commitment from the private sector, it would have been more difficult to reach a global agreement on the climate.

But the third was the most revolutionary: for the first time, a United Nations conference was going to open its doors to civil society.

Until Rio, only international non-governmental organisations that had consultative status with the Economic and Social Council (around 800 at the time) could participate. More than 3,000 civil society representatives, many from the local and national level, were at the Earth Summit.

Until Rio, only international non-governmental organisations that had consultative status with the Economic and Social Council (around 800 at the time) could participate. More than 3,000 civil society representatives, many from the local and national level, were at the Earth Summit.

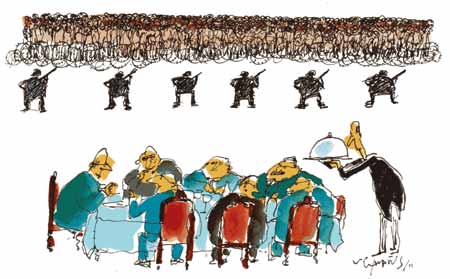

Obviously, the reaction of many governments was negative, and they managed to get the NGOs to meet in their own parallel and simultaneous forum, while only a few representatives attended the assembly of delegates. Since then, that has been the space carved out for civil society.

IPS has covered environmental issues since it was founded in 1964, and it had a great deal of credibility. I was director general at the time, and I went to talk to Strong to help him see that two simultaneous meetings held 40 km apart were certainly not what he would have wanted.

I then presented him with the idea that IPS could produce a daily newspaper about the conference which, distributed at both gatherings, could serve as a tool for communication and participation.

But I wanted to make sure that IPS could cover the conference and distribute the newspaper. Strong supported the idea, but warned me that if any country protested, only U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali could save me from being expelled, since only member states could circulate printed matter at a conference.

From Boutros-Ghali, a master of diplomacy and cryptic phrases, I was unable to obtain a definite guarantee. But I understood that he was in favour of it, as long as we did nothing that was indefensible. During the conference, he ignored protests from several countries about the presence of a non-governmental actor.

That is how TerraViva came out for the first time, with a 20- to 56-page Spanish edition (comprehensible to Portuguese-speakers), and a 12- to 14-page English edition. It was like putting together a real newspaper, and for IPS it was a new, creative experience, which gave birth to a high-level group of professionals.

Since 1992, TerraViva has been produced at U.N. conferences and other major events, which eventually included civil society gatherings like the World Social Forum.

TerraViva has played an unprecedented role in bolstering democracy and transparency at intergovernmental meetings.

Diplomats act on instructions from their governments, and when they have differences with other diplomats, these do not continue to rankle as personal issues outside of the meting. But when TerraViva reported that such-and-such a delegate had taken a stance that civil society did not accept, the participants in the NGO forum sought out the delegate in question and argued with him or her even in his or her hotel room.

Diplomats thus had to pay a formerly unknown personal price, and were forced to inform their governments when a certain position did not have the support of civil society.

Unfortunately, we have all-too-sufficient evidence that governments do not always listen to the voices of their voters.

On the climate front, after 20 years of twists and turns, we are returning to Rio with great expectations. But we have lost precious time in which the deterioration of the planet has accelerated and has become more glaring.

At the same time, the public has become more ecologically-minded than ever.

If Rio+20 fails to produce significant concrete results, the political system’s deficit of democracy will be evident. And TerraViva, once again, is here to generate participation and awareness – fundamental pillars of democracy.

* Roberto Savio is president emeritus of IPS, and was editor of the TerraViva produced at the 1992 Earth Summit.

Add to Google

Add to Google